Pokémon Sword & Shield have proven to be, despite the initial controversy, massive hits. While the roster of pocket monsters this time around might be minimal, the roster of fascinating characters is far from it. From your rival Hop to his older brother and champion, Leon, the various characters who appear throughout the game have attracted plenty of praise. The gym leaders, as usual, have also become very popular, from the muscle-bound Milo to the chubby Ice-aunt Melony and the spectral Allister.

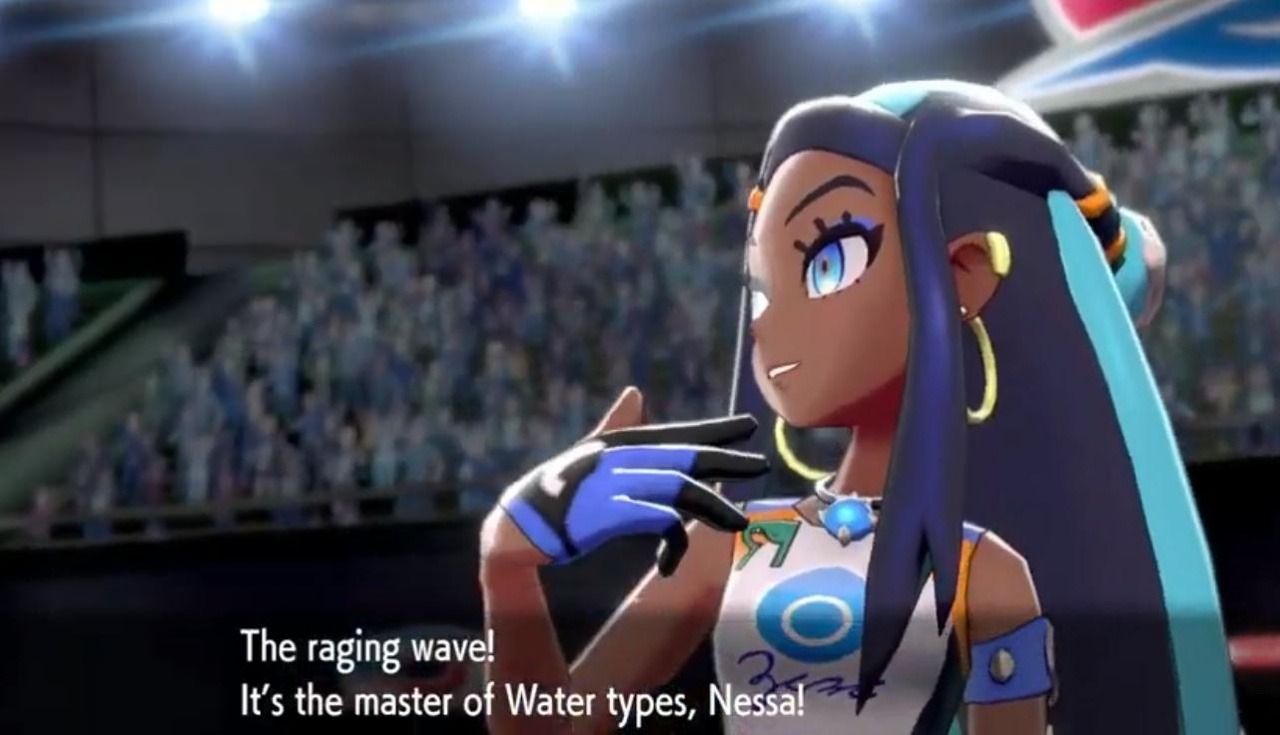

But the one who has dominated conversation is Nessa, the second gym leader players face in the games. Nessa gained initial popularity from her character design, being the newest, prominent woman of color in the decade-spanning franchise. Nessa isn't the first black gym leader in a Pokémon game. She follows Lenora and Iris from Black and White, Grant from X and Y, and Olivia from Sun and Moon, so it's odd that, while some love her, she's also stirred up more controversy for the games -- or, rather, an odd reaction from a certain section of Pokémon's fanbase.

Early on, there was an outcry against Nessa being black, with a subset of fans even denying her blackness by calling her "tan." This came to a head when a mod turning Nessa white was created.

Some people create mods to improve their gaming experience. In some cases, players constructed mods for Pokémon Sword & Shield to maximize performance or improve graphics as they saw fit. Typically, character models are altered in video games so that either a character's appearance can be "improved" or so that the player can have fun replacing one character with another. (The recent Batman/Catwoman swap in Arkham Knight is a prime example of the latter intent.) An example of this in Sword & Shield would be if a player replaced Nessa's character model with that of, say, Samus Aran from Metroid or Aerith from Final Fantasy VII. Mods like these make sense in so far as giving players a kick out of toying with the legal limitations of IPs.

But what about the intent to "improve" a character? This comes in two forms: actual improvements and opinionated improvements. An actual improvement just sharpens what already exists. Consider the mods that a classic game like Final Fantasy VII has received, offering far better-rendered models. The models' designs aren't changed on a fundamental level; they're just modernized.

Contrast this with mods that "improve" characters by making them "sexier," like mods that increase a female character's bust size or gives them skimpier clothing. These mods aren't improvements from a technical standpoint. The modder just likes these kinds of characters more for... personal reasons.

Now, this intent becomes even more complicated with Nessa: how do these modders justify that erasing a woman's race is "improving" the game?

Skin color has become a contentious issue in gaming as well as in other media, like comic books. Fan artists online over the summer had a long debate online about how to properly color darker-skinned characters, which spun out from a controversy surrounding how fan artists colored Nessa's skin. This then led to a wider discussion on the proper ways to illustrate dark skin. Many fans saw this discourse -- primarily started by people of color offering suggestions on how to properly illustrate their own skin tone -- as "policing."

Whether or not some fans were overly aggressive at young artists learning their trade is still debatable. Ultimately though, it almost doesn't matter, as the discussion became dominated by a subset of trolls who, in wanting to cause further anger, argued that Nessa wasn't black. She was actually, according to them, "very tan." Using this line of "logic" means that she'd actually be white (or at least fair-skinned).

This means that the Nessa mod exists really as a way to piss off the "social justice warriors" who dare offer advice on how to properly color people's skin in a way that's true to life. The mod succeeded in its aim to make a lot of people either upset or confused deliberately, but the bleaker undercurrent to all this is pretty simple: it's just plain whitewashing.

People of color aren't common in games, especially Japanese games. However, Pokémon has long been at the forefront of improving diverse representation with each new release, including allowing people to be able to customize their avatar's skin tone. The world of Pokémon is meant to feel like a fully-fleshed out one that you can immerse yourself in, after all, which is why it has universal, international appeal.

However, that is not to say that Pokémon is alone in this. Japanese media has in the last several years placed an increasing focus on improved diversity, especially on media intended for an international audience. Anime and video games coming from the country have increasingly presented racially diverse casts (to say nothing of its increasing LGBTQA representation). Consider the recent anime Carole and Tuesday, which features prominent racial diversity and was created by one of the most beloved anime directors of all time, Shinichiro Watanabe (Cowboy Bebop, Samurai Champloo and Space Dandy).

When people say "Japan doesn't care about racial diversity," they are making an incredibly reductive statement that ignores the reality of the situation. Statements like these -- and mods like this -- stand in direct opposition of progress. They are a statement to people of color that loudly says "We don't want you here." It creates an atmosphere of toxicity that alienates fans happy to see themselves represented in games.

But on top of that, it wreaks of immaturity. Either fans were angry at people explaining realistic skin coloring -- which is something all artists should learn if they want to improve -- or were angry that a fictional black woman simply existing in a video game, so much so that they altered character models to "fix" the "problem." This unneeded solution to video game diversity, to mod your personal experience so you don't have to see black people, screams of racism; evidence of an unwillingness to accept people exist outside of a bubble you craft for yourself and choose, instead, to hide in a space -- be it real or fictional -- where you won't encounter people different from yourself.